artists' books type

right

hand cast type as it appears after being taken out of the mould similar to the example above (Moxon). The cone-shaped part, created in the process of pouring the hot metal, is broken off in order to complete the process. Next to the metal type is a piece of much larger wooden type.

right: From Diderot's Encyclopedia we are able to glean an insight into the working life of the compositor. On the left of the picture, and in the centre, there are two skilled craftsmen who are "setting" type. They are both standing in front of two cases of type, one above the other. One contains "upper case" or "capital" letters, while the other contains lower case letters. Once the type has been set it is placed in a metal frame or "chase" and made ready for printing. It is important that all the type is level and at the same height, and in order to do this, the man on the right is "planing" the type by a process which involves striking a flat piece of wood with a hammer, which in turn pushes any protruding type into place without damaging it. If any of the type were too low, for example, it would not print, but if it were too high, it might print too dark or damage the paper or even damage the type.

Wood type was used extensively in the nineteenth and part of the twentieth century where large type sizes were required, when printing posters for example.

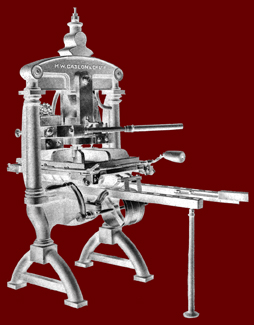

The Monotype caster

On the left is a stripped down Monotype caster. By using a keyboard, similar to that of a typewriter, the operator was able "set" lines of text consisting of individual pieces of type and, by continuing the process a whole page could be set at a time. Inevitably corrections had to be made and this meant re-casting a corrected line or even removing the offending individual letter with a pair of tweezers and the correct letter pushed in as a replacement.

Linotype casting differed from the Monotype process in that each line was cast as a whole unit called a "slug". Newspapers often favoured these machines.

There is far more detailed information on Martyn Ould's site THE OLD SCHOOL PRESS. For a clear illustrated and personal description of type setting there is no better source of information.

Type casting - the mould

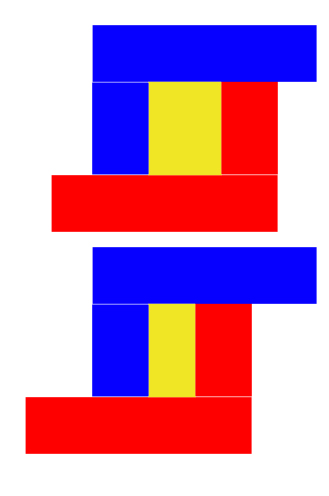

The red and blue "L" shapes represent the two parts of the mould. While the height of the letter remains constant the width is changed by sliding the two parts one against the other. The yellow represents the face of the type where the wider shape would be required for letters such as M and W, and the narrow shape would be used for I or J.

The constant height machine was a removable part of the Monotype caster. Every time the type size was changed the constant height mechanism would also be changed. The example on the left hand photograph is for nine points; if a type size of twelve points was required then the constant height mechanism would need to be changed.

This mechanism is not very different from the kind of mould that Gutenberg may have used. In basic terms the mechanism (left) is certainly a mechanical version of the mould described by Moxon (above). In order that type may print clearly all the small pieces of type must be of the same height (this is the distance from the face to the foot of the shank). However, the width of the letters is variable; the letter I is obviously narrower that the letters M or W. In order to understand the problem in creating such a mechanism, it is probably easier if one considers capital (upper case) letters.

In order to overcome this difficulty a mould was created that consisted, in its simplest terms, of two interlocking L shaped pieces (see above). The molten metal was poured in to the mould and the piece of type was formed by a combination of mould and matrix. The "matrix" on which the letter had been punched was situated at the opposite end (the underside) (lower photograph).